The order Multituberculata, informally also known as 'multis', is a diverse lineage of Mesozoic to early Cenozoic mammals that occupied a rodent-like niche. They appear first in the late Jurassic and are last known from the early Oligocene. The late Triassic haramiyids were sometimes considered as early multituberculates. More complete fossils have recently shown that haramiyids are a very different group of early mammals. But even without haramiyids, multituberculates existed for a time span of about 100 million years, the undisputed record for an order of mammals.

Multituberculates do not belong to any of the groups of mammals living today: the primitive egg-laying monotremes and the more advanced marsupials and placentals, both also known as therians. The relationships of the multituberculates to these groups are still debated. Multituberculates have been considered as either a group that branched off even before the monotremes, as close relatives of the monotremes or as sister group of the therian mammals. Anyway, multituberculates were clearly very mammal-like, both in details of the internal anatomy, like the structure of the middle ear with the three auditory ossicles, and in external appearance, like the recently demonstrated possession of hair (see below). The anatomy of the pelvis suggests that multituberculates did not lay eggs like monotremes but gave birth to very small, immature young like marsupials.

In the late Cretaceous multituberculates were widespread and diverse in the northern hemisphere, making up more than half of the mammal species of typical faunas. Although some lineages became extinct during the faunal turnover at the end of the Cretaceous, multituberculates managed very successfully to cross the K/T boundary and reached their peak of diversity during the Paleocene. They were an important component of nearly all Paleocene faunas of Europe and North America, and of some late Paleocene faunas of Asia. Multituberculates also were most diverse in size during the Paleocene, ranging from the size of a very small mouse to that of a beaver.

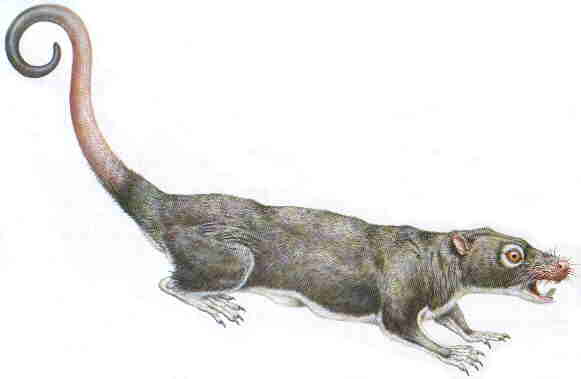

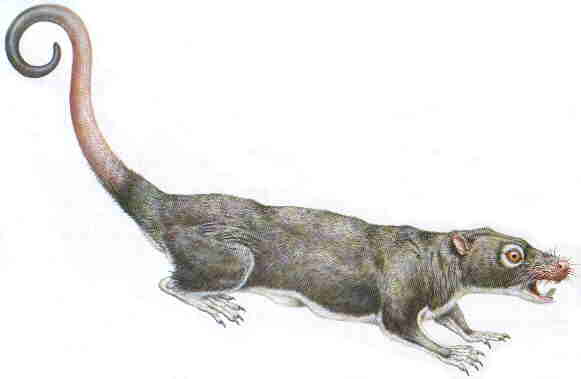

Figure 1: Reconstruction of the Paleocene multituberculate Ptilodus, about 50 cm in length. From Cox (1998).

Ptilodus is a typical medium-sized multituberculate from the Paleocene of North America. It is known from a nearly complete skeleton discovered in Canada, which shows that Ptilodus can best be compared with todays squirrels. The skeleton of Ptilodus shows several adaptations for life in trees, for instance sharp claws. Like in squirrels, the foot of Ptilodus was very mobile and could be reversed backward, which allowed the animal to climb down trees with its head pointing downward. A marked difference from squirrels is the long prehensile tail, which Ptilodus used like a fifth limb when climbing in trees.

The dentition of Ptilodus and other multituberculates

is most similar to rodents in the enlarged front teeth,

especially the pair of lower incisors, which are followed by a

gap (called diastema) in the lower jaw. The last lower premolars

of most multituberculates form large, serrated blades. This type

of teeth is called plagiaulacoid after the Mesozoic

multituberculate genus Plagiaulax. Several groups of

mammals have independently developed plaugiaulacoid teeth,

although not to the same degree as multituberculates like Ptilodus:

The back of the multituberculate jaw was occupied by a battery of molars that formed a grinding mechanism. These molars carried several longitudinal rows of many small cusps (or tubercles), which is the origin of the name Multituberculata.

Figure 2: Skull of Ptilodus montanus from the middle Paleocene of Montana, U.S.A, showing the blade-like lower premolar. After Miao (1993).

The diet of multituberculates is a long debated issue. Following the analogy to rodents, it could be assumed that multituberculates were herbivores. However, even todays rodents do not all feed on vegetable material only. In addition, the blade-like lower premolar must be taken into account. The recent rat-kangaroos, which share this feature, include not only herbivores but also omnivores that feed on plants, insects or even carrion. A similar diet can be imagined for multituberculates, too. In this scenario, the enlarged incisors would be have been used for picking up and killing insects or other prey. The blade-like premolars could have served both for biting hard shelled seeds and for chopping up small prey.

Members of a specialized family of multituberculates, the Taeniolabididae, can be considered more confidently as herbivores. Like rodents, taeniolabidids (and some related multituberculate families) had developed gnawing teeth with a self-sharpening mechanism. Only the front side of the incisors is covered with hard enamel. The rest of the tooth consists of softer material which is worn away more easily. Therefore the tooth has always a sharp cutting edge at the front. The blade-like premolars are strongly reduced, whereas the molars form enlarged, complex grinding surfaces with an increased number of cusps. The type genus of the family is Taeniolabis from the early Paleocene of North America. This beaver-sized animal is the largest known multituberculate. Taeniolabis had a massive skull, low in profile, with a short, blunt snout. Its well-developed gnawing teeth and complex molars are strong evidence that Taeniolabis, unlike most other early Paleocene mammals, had specialized on vegetable diet.

Figure 3: Skull of Taeniolabis taoensis from the early Paleocene of New Mexico, U.S.A, about 180 mm in length. Note development of gnawing teeth. From Sloan (1981).

Remarkable fossils from the late Paleocene of China are known for a second taeniolabidid, Lambdopsalis. The skeleton of Lambdopsalis shows specializations for digging, so this multituberculate was probably living in burrows. Well-preserved skulls indicate that the ear of Lambdopsalis was inefficient for hearing high-frequency airborne sound, but well-adapted for hearing low-frequency vibrations, which would be useful for a burrowing animal. Lambdopsalis was obviously a favorite prey of carnivorous mammals, as evidenced by its occurrence in coprolites (fossilized excrements) of carnivores at a Chinese locality. Absolutely unique is the fact that these coprolites preserve fossilized hair of the prey, including that of Lambdopsalis, which is very similar in structure to hair of living mammals. This is the only direct evidence that the extinct multituberculates had hair, and at the same time the oldest known occurrence of fossil mammalian hair.

After the diversity of multituberculates had reached a maximum in the Paleocene, it started to declide towards the end of this epoch. This may be due to competition with an increasing number of placental herbivores, especially with the archaic hoofed mammals called condylarths and with primates. In the latest Paleocene true rodents appeared as additional competitors that were particularly close in ecology. A number of multituberculate genera survived into the Eocene, but few new genera developed, and multituberculates became extinct in the early Oligocene.

An odd group of late Mesozoic

to early Cenozoic mammals from the ancient landmass of Gondwana

is worth mentioning here since it may represent a southern

radiation of multituberculates. These poorly known animals,

appropriately called gondwanatheres, were first found in the late

Cretaceous (Gondwanatherium, Ferugliotherium) and early

Paleocene (Sudamerica) of South America. Rare fossils have

recently also turned up in the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar and

India, all former parts of disintegrating Gondwana. At least Gondwanatherium

and Ferugliotherium had enlarged incisors for gnawing.

But the most striking feature of advanced gondwanatheres like Gondwanatherium

and Sudamerica are the very high-crowned molars. In

the later Tertiary many groups of plant-eating mammals have

developed high-crowned teeth to cope with the spreading grasses

that strongly wear down teeth. However, such teeth are unique for

the Mesozoic and the earliest Cenozoic, and we do not know what

triggered their early evolution in gondwanatheres. Grasses did

not appear in South America until much later, and fossils of Sudamerica

were probably deposited in a mangrove swamp.

An odd group of late Mesozoic

to early Cenozoic mammals from the ancient landmass of Gondwana

is worth mentioning here since it may represent a southern

radiation of multituberculates. These poorly known animals,

appropriately called gondwanatheres, were first found in the late

Cretaceous (Gondwanatherium, Ferugliotherium) and early

Paleocene (Sudamerica) of South America. Rare fossils have

recently also turned up in the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar and

India, all former parts of disintegrating Gondwana. At least Gondwanatherium

and Ferugliotherium had enlarged incisors for gnawing.

But the most striking feature of advanced gondwanatheres like Gondwanatherium

and Sudamerica are the very high-crowned molars. In

the later Tertiary many groups of plant-eating mammals have

developed high-crowned teeth to cope with the spreading grasses

that strongly wear down teeth. However, such teeth are unique for

the Mesozoic and the earliest Cenozoic, and we do not know what

triggered their early evolution in gondwanatheres. Grasses did

not appear in South America until much later, and fossils of Sudamerica

were probably deposited in a mangrove swamp.

Some gondwanatheres were previously considered as early member of the Xenarthra (armadillos, anteaters and sloths) due to somwhat similar teeth and their geographic occurence in South America, the home of the xenarthrans. Detailed studies of the dentition, including the microstructure of the enamel covering the teeth, have suggested that gondwanatheres may instead be the first 'multis' known from southern continents. More complete fossils will hopefully resolve the debate on the relationships of this enigmatic group from Gondwana.

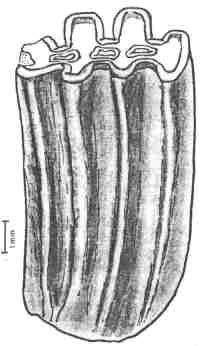

Figure 4: High-crowned tooth of the gondwanathere Sudamerica ameghinoi from the early Paleocene of Patagonia, Argentina. From Scillato-Yané & Pascual (1985).

Sources of figures:

Cox, B. (editor) 1988: Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. Macmillan London Limited.

Miao, D. (1993): Cranial morphology and multituberculate melationships. In: Szalay et. al. (editors), Mammal Phylogeny, volume 1. Springer-Verlag New York, Inc.

Sloan, R. E. (1981): Systematics of Paleocene multituberculates from the San Juan Basin, New Mexico. In: Lucas et. al. (editors), Advances in San Juan Basin Paleontology, University of New Mexico Press.

Scillato-Yané, G. J. & Pascul, R. (1985): Un peculiar Xenarthra del paleoceno medio de Patagonia (Argentina). Su importancia en la sistemática de los Paratheria. Ameghiniana 21, 173-176.